Catching Up With . . . Ray Arsenault

The Freedom Writer

by Brooke C. Stoddard '69

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” --Martin Luther King Jr.

Ray’s lifelong interest in the past grew out of a fascination with a complicated family background worthy of the proverbial American “melting pot.” As the son of a Naval photographer whose career required frequent relocations—including long stretches traveling the world on aircraft carriers—Ray found a refuge of sorts in digesting family stories that grounded his identity in history and geography.

Ray’s lifelong interest in the past grew out of a fascination with a complicated family background worthy of the proverbial American “melting pot.” As the son of a Naval photographer whose career required frequent relocations—including long stretches traveling the world on aircraft carriers—Ray found a refuge of sorts in digesting family stories that grounded his identity in history and geography.

“On my mother’s side,” he explains, ”I encountered an intriguing cast of characters--nearly four centuries of Cape Cod fishermen, sea captains, Congregationalist ministers, abolitionists, and educators, including the founder of America’s first academy devoted to the science of navigation.” In the mix was his maternal great-grandfather, a popular lantern-slide lecturer known for his performances of Ben Hur and Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, who at the urging of his second wife—a young Norwegian divorcee—left New England for Hollywood in 1926 to seek his fortune in the film industry. He never made it in the movies but remained in California for the rest of his life.

The family’s New World saga began with Stephen Hopkins, the only Mayflower passenger who had already been to America, having spent two years in Jamestown. Shipwrecked in 1611 en route to Virginia near the coast of Bermuda, Hopkins led a brief island mutiny against the leader of the expedition, Virginia’s new governor. Condemned to death but later pardoned, he apparently served as the inspiration for the roguish, picaresque character Stephano in Shakespeare’s fictional account of the Bermuda shipwreck, The Tempest.

If this was not enough to pique Ray’s interest in family lore, his mother’s father was a Norwegian-born photographer and printmaker who came to the United States in 1912, before enlisting in the U. S. Army during World War I. The photographer’s father was a folk singer, recording artist, and theatrical celebrity widely known as “the singing barber of Norway.” He was also a noted political dissident arrested and tried for sedition after caustically lampooning the King of Sweden in 1903.

Ray’s father’s family was a bit more conventional, migrating from France to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the late 17th-century, and remaining for generations in a cluster of Acadian villages close to the sea. Working as fishermen, harbor pilots, and farmers, the family eventually fell into the common Maritime Provinces pattern of moving back and forth between Canada and New England, settling wherever the economy looked most promising. Ray’s father was born in Maine but grew up in New Bedford, where his father worked as a salvage and bridge construction diver. After her husband drowned during a weekend outing at a lake in 1931, Ray’s grandmother and her seven children under the age of ten returned to New Brunswick in a desperate attempt to survive the depths of the Great Depression.

Unfortunately, it proved impossible for the family to stay together, and at age 14, Ray’s father, the oldest son, was given $22, a ticket to Boston, and the addresses of Massachusetts relatives who might have a spare bed for an orphan. The times were tough for just about everyone, of course, and he quickly ran out of options. Eventually he took refuge in an abandoned farmhouse on Cape Cod, and in a fortunate turn of events almost worthy of a Horatio Alger novel, he was soon rescued by a good Samaritan (the Norwegian photographer, Ray’s maternal grandfather) who invited him to live with his family, which included three young children--two twin daughters and a son—and a wife with deep New England roots.

In his new circumstances, the French boy flourished, becoming fluent in English, learning skills that would later propel his career as a photographer, falling in love with one of the twins, and marrying her in 1944 while he was on leave from his Naval service in the Pacific as a reconnaissance photographer flying in B-24 bombers. As Ray often tells his students, the historical process is best understood as a series of contingent events and not as the result of deterministic forces, and the highly improbable merger of the two sides of his family is a good case in point. In his view, the presence of unpredictability and irony is what makes history so fascinating, continually providing surprises and unexpected discoveries that inspire passionate engagement and intellectual curiosity.

“In family stories, as in the broader historical narrative,” Ray reminds us, “distinguishing myth from reality is never easy, and the would-be historian must develop a wary eye for misinformation and hyperbole.” In his case, developing a healthy level of skepticism was aided by the cultural confusion and personal insecurity that characterized his early years. Shifting back and forth between North and South every two years or so, he attended twelve schools before graduating from high school on Amelia Island, Florida, in 1965. Always being the new kid, he had to adapt to the challenges of moving from one regional culture to another, a process, he insists, that either makes you or breaks you. Either way the experience is deeply affecting.

Ray split his childhood between the Yankee Northeast and the ex-Confederate South during a time of social and cultural turmoil driven by a quickening struggle for civil rights. Long before the term “culture war” became fashionable as a way of labeling the divisions that have roiled American society in recent decades, Ray was caught in a conflict he could not escape. Identifying as a Northerner but living in the South, in what sometimes felt like enemy territory, he developed a deep interest in all matters related to regional culture, racial discrimination, and civil rights.

This consuming curiosity had a lot to do with the local culture and racial demography of the communities in which he lived. For him, the regional contrast was accentuated by the racial mix of his hometown of Harwich, Massachusetts, which, unlike the much whiter surrounding towns, boasted a non-white population of roughly 35 percent. Most of these non-whites were mixed-race Cape Verdeans, often referred to locally as “Portugese.” Many descended from families recruited in the late-19th or early-20th century to work either in the whaling industry or, more commonly, to plant and harvest cranberries on the scores of bogs that dotted Harwich’s landscape. By the 1950s, the vast majority of Harwich’s Cape Verdean residents had moved into other occupations, joining a wide spectrum of middle-class employment ranging from teachers and medical professionals to policemen, firemen, and public officials. While residential segregation and some discriminatory customs persisted, the local Portugese community enjoyed more opportunities and higher status than minorities living in more typical American communities, North or South.

“The stark cultural contrast between Harwich and the communities where I lived In Virginia and Florida,” Ray remembers, “forced me to wrestle with differing attitudes toward race and civil rights. Following a period of confusion and doubt, I drew upon my family’s longstanding liberalism on matters of race and became increasingly determined to speak out on civil rights issues.” One family story that inspired him occurred in Pensacola in 1956 during the Montgomery Bus Boycott: “My tiny but feisty, Yankee-chauvinist grandmother lived with us at the time, and whenever we traveled on a city bus she insisted on riding in the back of the bus with the Black passengers, not in the front where whites traditionally sat. I remember how the white passengers scowled at us, but at the time I had no idea of what was really going on. Only later, when I finally understood the statement my grandmother was trying to make, did I feel pride in her symbolic stand against racism.”

Two other experiences, both in 1963, helped shape Ray’s evolving commitment to civil rights. During the last week of August, after two years of living in Maryland just outside of Washington, Ray and his family moved back to Florida, where they had lived from 1955 to 1957. Coming back from a brief visit with relatives on Cape Cod, they stopped for the night at a suburban Maryland motel before driving on to Florida. The exact date was August 27, the night before the March on Washington. When his exhausted parents went to the room for a nap, Ray went to the swimming pool which, to his surprise, was filled with a hundred or more bathers, most of whom were African Americans planning to attend the march. Several of the marchers engaged him in conversation, and for the next two hours they talked about what they expected to experience the next day. “Boy, if you want to see history in the making, bring your family to the Lincoln Memorial tomorrow,” one marcher urged, “Martin Luther King and 200,000 others seeking freedom and equality will be there.”

“Thus began one of the transformative episodes of my life,” Ray recalls. “Intoxicated by meeting the marchers, I rushed back to my family and excitedly told them ‘We can’t drive to Florida tomorrow. We have to go to the march.’ Well, in the Hollywood version of this story, we would have gone to the march, but in real life we departed for Florida on schedule the next morning, with me stewing in the back seat, convinced I had missed my one chance to be a part of history. Later that week, when I read the press accounts of what had happened, I was even more distressed.” (Ray made it to the 50th anniversary March; see photo.)

“Thus began one of the transformative episodes of my life,” Ray recalls. “Intoxicated by meeting the marchers, I rushed back to my family and excitedly told them ‘We can’t drive to Florida tomorrow. We have to go to the march.’ Well, in the Hollywood version of this story, we would have gone to the march, but in real life we departed for Florida on schedule the next morning, with me stewing in the back seat, convinced I had missed my one chance to be a part of history. Later that week, when I read the press accounts of what had happened, I was even more distressed.” (Ray made it to the 50th anniversary March; see photo.)

To make matters worse, for a brief period that fall he was a student at Jacksonville’s Nathan Bedford Forrest High School, an overcrowded, underfunded school named for the former slave trader and Confederate general who served as the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Fortunately, he left after six days, transferring to a much better and smaller school thirty miles north on Amelia Island, where his paternal grandmother, an aunt and uncle, and several cousins lived, and where he soon met a classmate who later became his wife and soulmate.

Even so, there was no escaping the gathering racial crisis in the region. The transfer to an island beach community, where Ray lived with his grandmother for the next two years, introduced him to small-town Southern life at a time when the specter of school desegregation dominated the local mindset. Beyond the island’s seductive beach culture--with its surfboards and bikinis--was a fearful white majority determined to preserve its Jim Crow heritage of cradle-to-grave segregation. Ray discovered just how deep this heritage was in late November 1963 when he witnessed the cheering that erupted when his fellow students heard the news that the liberal Yankee President, John F. Kennedy, had been assassinated in Dallas. Their first thought, it seemed, was “Now they wouldn’t have to go to school with black people.”

“I don’t think I ever felt so alone as on that dark day when I realized the depth of the racism around me,” Ray recalled. “On one level, I loved my high school years, when I was mentored by several inspiring teachers, and when I enjoyed life beyond the classroom socializing with a wide circle of friends and playing basketball and baseball on two of the best teams in the state. But on another level, there was always a dark cloud of racial hatred and discrimination hanging over me.”

“Going off to Princeton in 1965—the year of the Selma-to-Montgomery march and the Voting Rights Act—was a liberation for me,” Ray remembers, “a chance to escape the turmoil of the Jim Crow South and to live and learn in a nurturing environment where humane ideals and the life of the mind were valued.” Arriving on campus for the first time, he felt as if he had found the proverbial “Emerald City,” even after he came back to earth living in drab and dingy Brown Hall and working as a busboy in the dining commons. Academically, Princeton exceeded all of his expectations, and he began to blossom as an intellectually curious and talented student in the humanities and the social sciences. His only disappointment was failing to make Princeton’s basketball team, though a sobering experience guarding the future NBA All-Star Geoff Petrie during a 1966 Cane Spree game—Ray “held” him to 18 points in an 8-minute quarter—confirmed he was not cut out for basketball stardom.

Sophomore year brought Ray to an unexpected fork in the road. Hoping to be promoted to a cushy position as a busboy captain, he stumbled into one of the contingent moments of his life. On the evening before the new captains were to be chosen, while he was working at a special Friday night “dating parlor” (soft music, flowers, candlelight, linen tablecloths) in Holder Hall, he tripped on the stairs, dropping more than a hundred plastic glasses near the entrance of the parlor and spoiling the romantic mood for the students and their dates. That was the moment he knew there would be no promotion; his career as a busboy was over. Yet as a scholarship student he was still entitled to a job, which soon materialized in the form of a research assistantship with one of the budding stars of the history department, Sheldon Hackney, who would go on to become Princeton’s provost and the president of Tulane and Penn, and eventually the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

A specialist in Southern political and civil rights history, Hackney was a Birmingham native and Yale Ph.D. who had studied with the nation’s most prominent Southern historian, C. Vann Woodward. He was also closely connected to the civil rights movement through his wife Lucy’s Montgomery-based parents—the noted voting rights activist Virginia Durr, and her attorney husband Clifford, both of whom were close friends and supporters of Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. Working for such an inspiring mentor and role model profoundly changed Ray’s life, bringing him into contact with an array of civil rights activists and launching his career as an engaged scholar.

During two years as a research assistant, Ray was given the opportunity to help plan the first course on Southern history taught at Princeton in more than a decade, to compile a casebook of documents on the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and to research the roots of Southern culture’s proclivity for violence. Along the way, he also helped prepare Hackney’s dissertation on Populist and Progressive politics in Alabama for publication as a book, which served as a model for Ray’s Joline Prize-winning senior thesis on the relationship between Populism and Progressivism across the region.

While all this was happening, Ray was also learning about married life alongside his high-school sweetheart Kathy, with whom he had eloped in June 1967, the same month he began his research assistantship. Part of a prominent Southern family that had lived on Amelia Island since the 18th-century, Kathy, who would later finish her degree at Wellesley and go on to be a university library dean, had been a student at Agnes Scott College in Atlanta, a little-known institution among Princetonians until its 1966 College Bowl team defeated Princeton in what one magazine called “The Greatest Upset in Quiz Show History.” At Princeton, Kathy worked at the Firestone Library circulation desk, and the couple shared a Witherspoon Street duplex with classmate Doug Hensler and his wife, another of Princeton’s roughly fifty undergraduate married couples. With money tight, Ray and Kathy kept the wolf from the door by earning a few dollars babysitting for the Hackneys two nights a week, an experience that strengthened the bond between the two families.

After graduating magna cum laude, Ray, with Hackney’s help, won a coveted graduate fellowship to study with C. Vann Woodward at Yale. But, unfortunately, he received his draft notice the same day the acceptance letter arrived. This twist of fate set him off on a two-year detour, beginning with four months at Naval Officer Candidate School in Newport, where his strong antiwar feelings prompted him to resign after receiving orders to serve as a combat information center officer on a guided missile cruiser.

Honorably discharged from the Navy but still subject to the draft, he took a job teaching high school math on Cape Cod. He taught his first class on January 6, 1970, his 22nd birthday, and “truly loved teaching from the start.” For the next eighteen months, with a draft deferment in hand, he taught both advanced math and special noncredit history courses on politics and radical dissent, coached junior varsity soccer, became actively involved in progressive politics and the antiwar movement, and even ran a counterculture coffee house and folk music venue during the summer. “It was both exhilarating and exhausting, particularly for Kathy who was commuting 180 miles roundtrip to Wellesley by bus,” Ray remembers. But by 1971 graduate school and the history profession beckoned.

Offered fellowships by both Harvard and Brandeis, he took a chance and chose the latter. “Brandeis was a better fit for me,” he insists. “At the time it actually had a stronger faculty in American history than Harvard, and it was also a major center of what was then called ‘the new social history,’ the kind of democratized, interdisciplinary history that I wanted to write and teach.” At Brandeis, he benefited from an intellectually and politically vibrant campus—and from studying with several of the nation’s most talented and imaginative historians. During his five years there, his interest in the history of race relations and white supremacist ideology and institutions deepened and broadened to include the modern and contemporary Black liberation struggle in southern Africa, which became the subject of his first published article in 1972. He went on to write his Ph.D. thesis on Arkansas’s Jeff Davis, a pre-World War I demagogue known as “The Wild Ass of the Ozarks,” which became the title of Ray’s first book, published in 1984.

In 1976, Ray accepted a position at the University of Minnesota, where he remained for four years (or as Florida-born Kathy put it, “four frigid winters”). In 1980, the Arsenaults left the “Deep North” (though for seven years Ray returned to Minnesota each summer to run Fulbright regional culture institutes for foreign teachers) and relocated to St. Petersburg and the University of South Florida, where Ray taught history and ran the campus honors program and Kathy worked in the university library. During the next twenty years in the “Sunshine City,” they raised two daughters and became deeply involved in a wide variety of community organizations and issues, ranging from voting rights and civil liberties to criminal justice reform, historic preservation and environmental sustainability.

Eventually, Ray became one of St. Petersburg’s most prominent social activists, advocating for the interests of African Americans, immigrants, the homeless, and other marginalized and vulnerable groups. He helped found an African American history museum and culture center, and fought against overdevelopment, environmental racism, and violations of constitutionally protected civil liberties. For 35 years, he served as president of the local ACLU and as a member of Florida ACLU’s Board of Directors, including two terms as state president. Along the way, he received numerous awards recognizing his commitment to civil and human rights and social justice.

Most of his time, of course, was spent either in the classroom, where he won several teaching awards, or busily researching and writing works of history. In the 1980s, his academic interests branched out to include Florida, a woefully understudied state despite its rising political and demographic profile, and in 1996 he became the founding co-editor of a Florida History and Culture Book Series (published by the University Press of Florida) that eventually produced 50 volumes. Seven years later, he co-founded an interdisciplinary graduate program on Florida Studies designed to explore the state’s distinct regional culture as a bridge between the South and Latin America. In recognition of his contributions to Florida history, he later received lifetime achievement awards for writing from both the Florida Historical Society and the Florida Humanities Council.

Branching out into environmental, urban, and cultural history, Ray published a prize-winning article in 1984 on “the air conditioner and Southern culture,” and spent the next year in France as a Fulbright lecturer studying French regional cultures. In 1988, he published his second book, a centennial history of St. Petersburg, and three years later a third book commemorating the 200th anniversary of the Bill of Rights. Edited books on civil rights journalism and Florida’s environmental history followed, before he turned to the most important project of his career, writing the first book-length study of the Freedom Rides of 1961.

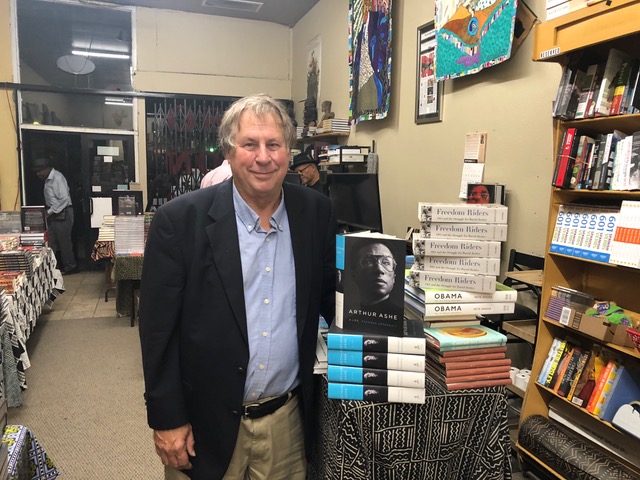

In 2006, after eight years of research and writing, Ray published Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice as part of Oxford University Press’s “Pivotal Moments in American History” series, co-edited by two of his former teachers, James McPherson of Princeton, and David Hackett Fischer of Brandeis. The rationale for initiating the series was to bring the focus of historical writing back to storytelling and the construction of analytical narratives that stress contingency. Ray did not disappoint his mentors, producing a stirring and thought-provoking account of the courageous 436 Freedom Riders who risked their lives to advance the civil rights struggle through nonviolent direct action. (See photo of Ray in front of Freedom Rider mug shots.)

In 2006, after eight years of research and writing, Ray published Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice as part of Oxford University Press’s “Pivotal Moments in American History” series, co-edited by two of his former teachers, James McPherson of Princeton, and David Hackett Fischer of Brandeis. The rationale for initiating the series was to bring the focus of historical writing back to storytelling and the construction of analytical narratives that stress contingency. Ray did not disappoint his mentors, producing a stirring and thought-provoking account of the courageous 436 Freedom Riders who risked their lives to advance the civil rights struggle through nonviolent direct action. (See photo of Ray in front of Freedom Rider mug shots.)

Widely praised, the book won the Southern Historical Association’s prize for the year’s most important work in Southern history. It also inspired a two-hour documentary directed by Stanley Nelson for PBS’s American Experience (still available on PBS, with Ray as the principal commentator). The powerful film--which won Emmys for writing, editing, and documentary excellence, plus a Peabody Award—has been seen by tens of millions of viewers across the world, providing unprecedented exposure for a group of long-forgotten heroic figures. With this rediscovery, the former Freedom Riders were suddenly in demand as speakers who could provide living witness to the nonviolent struggle that changed American life in the 1960s. A number were invited to the White House, and 180 of them, along with Ray, appeared on the Oprah Winfrey Show in May 2011 to commemorate the 50thanniversary of the Rides.

“Interviewing and getting to know hundreds of Freedom Riders had a profound effect on me,” Ray recounts. “Even In the face of brutal repression, they refused to strike back, remaining true to their belief in nonviolence and what they called the Beloved Community. They were the foot soldiers of the movement, unsung heroes whose stories of moral and physical courage were a revelation and an inspiration.”

Beginning in 2006, Ray began leading weeklong civil rights bus tours of the Deep South with former Freedom Riders onboard. Each summer he led students and teachers and others through a life-changing encounter with the movement and its legacy, highlighted by interacting with movement veterans and visiting civil rights museums, historic courtrooms, Black churches, and other “freedom” sites.

These tours were just part of Ray’s burgeoning career as a public historian, and over the next fifteen years he served as a consultant for dozens of museums, teacher institutes, and documentary film projects, many of which focused on civil rights issues. He delivered hundreds of public lectures across the U.S. and a dozen foreign countries, often as part of the Organization of American Historians’ Distinguished Lecturer program or under the auspices of the Fulbright Commission or USIA. He also taught in both London and at the University of Chicago for a semester and ran institutes on American political and social history in Greece, Turkey, and Jordan.

In 2009, as part of the Abraham Lincoln Centennial celebration, Ray helped organize a commemorative event marking the 70th anniversary of the Black contralto Marian Anderson’s historic Easter 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial. Published earlier in the year, his book The Sound of Freedom: Marian Anderson, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Concert That Awakened America generated considerable interest in this civil rights milestone (Ray calls Anderson “the Jackie Robinson of classical music”), and a decade later the book became the basis for a 2-hour American Masters PBS documentary on Anderson, with Ray as the principal commentator.

Much of this activity was made possible by Ray’s ascension to an endowed professorship of Southern history in 1998. Named for 83-year-old John Hope Franklin--one of the world’s most distinguished African American historians and the recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom and more than 150 honorary degrees--this position brought a reduced teaching load, increased funding for travel and research, and the daunting responsibility of carrying on Franklin’s legacy. After retiring from the University of Chicago in 1980, Franklin spent a month each winter in St. Petersburg, providing Ray with the opportunity to develop a deep intellectual bond and close friendship with a living legend. Paying tribute to Franklin in 2009, Ray devoted most of his essay in our 40th Reunion Book to an admiring profile of his friend, who died earlier in the year at age 94.

Another cherished friend and mentor became the subject of his next book, Dixie Redux: Essays in Honor of Sheldon Hackney, an edited collection published in 2013, just after Hackney’s death following a long battle against Lou Gehrig’s disease. (See photo of Ray with Sheldon Hackney and friends.) Five years later, after nine years of research and writing, Ray completed a long-awaited biography of Arthur Ashe, the great African American tennis player and humanitarian who died of AIDS in 1993. An enthusiastic but mediocre tennis player, Ray envisioned his study of Ashe as the third book of a trilogy (along with Freedom Riders and The Sound of Freedom) devoted to

Another cherished friend and mentor became the subject of his next book, Dixie Redux: Essays in Honor of Sheldon Hackney, an edited collection published in 2013, just after Hackney’s death following a long battle against Lou Gehrig’s disease. (See photo of Ray with Sheldon Hackney and friends.) Five years later, after nine years of research and writing, Ray completed a long-awaited biography of Arthur Ashe, the great African American tennis player and humanitarian who died of AIDS in 1993. An enthusiastic but mediocre tennis player, Ray envisioned his study of Ashe as the third book of a trilogy (along with Freedom Riders and The Sound of Freedom) devoted to  underappreciated but important historical figures who advanced the civil rights struggle. Widely acclaimed as a beautifully written and authoritative work, Arthur Ashe, A Life was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times, the Boston Globe, and the Wall Street Journal; and Barack Obama listed it as one of his favorite books of the year. Ray appreciates all the praise but laments that writing it did nothing to improve his weak backhand.

underappreciated but important historical figures who advanced the civil rights struggle. Widely acclaimed as a beautifully written and authoritative work, Arthur Ashe, A Life was named one of the best books of the year by the New York Times, the Boston Globe, and the Wall Street Journal; and Barack Obama listed it as one of his favorite books of the year. Ray appreciates all the praise but laments that writing it did nothing to improve his weak backhand.

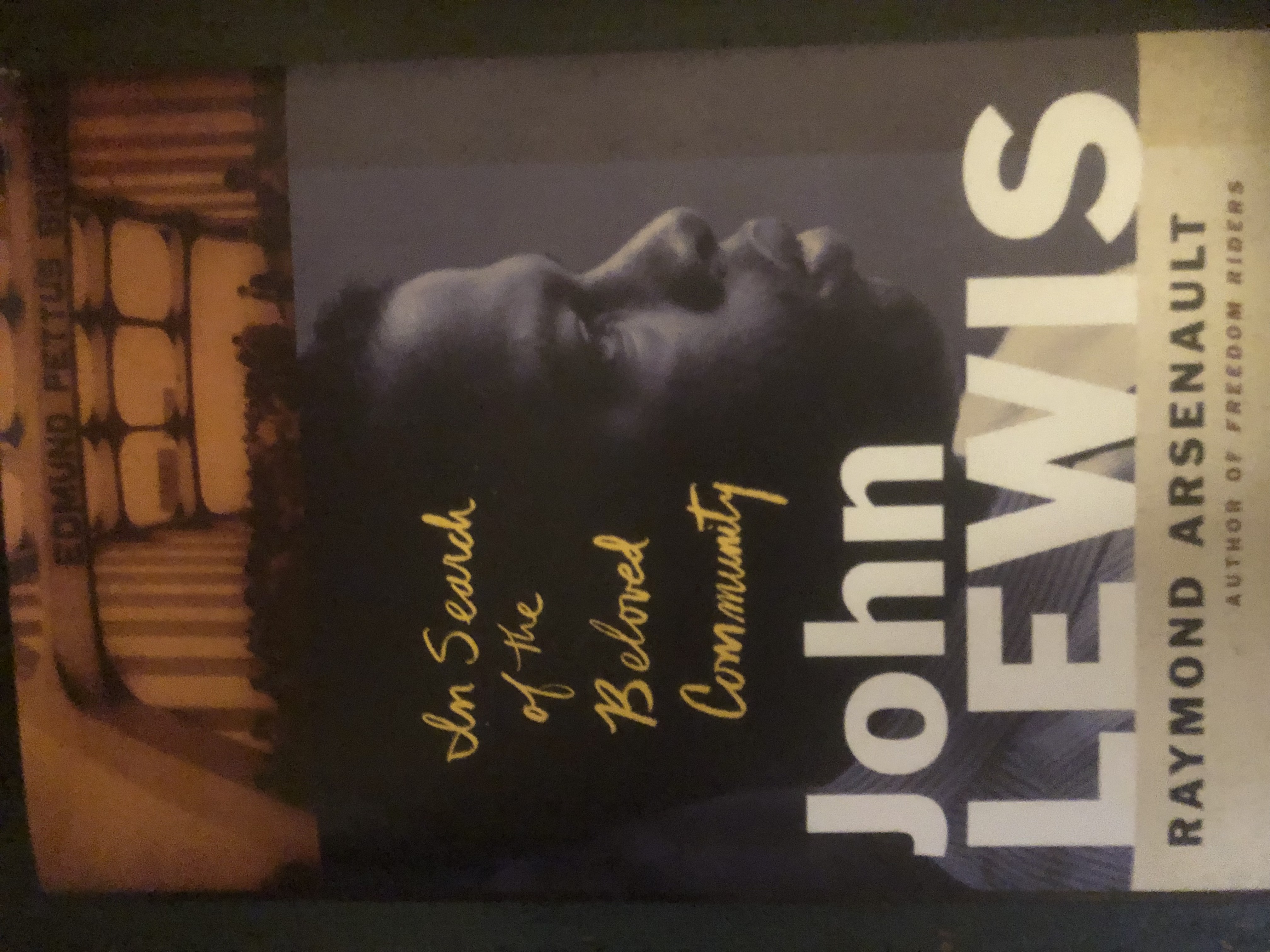

Ray’s latest book—due out this winter from Yale University Press—is John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community, the first comprehensive biography of the civil rights icon (photo, right). Ray enjoyed a twenty-year friendship with Lewis prior to his death in 2020, an unusual situation that gave him added insight into Lewis’s character but also complicated the task of maintaining a measure of scholarly detachment. Like those of Marian Anderson and Arthur Ashe, Lewis’s sainted life, Ray concedes, sometimes seems almost too good to be true.

Community, the first comprehensive biography of the civil rights icon (photo, right). Ray enjoyed a twenty-year friendship with Lewis prior to his death in 2020, an unusual situation that gave him added insight into Lewis’s character but also complicated the task of maintaining a measure of scholarly detachment. Like those of Marian Anderson and Arthur Ashe, Lewis’s sainted life, Ray concedes, sometimes seems almost too good to be true.

One telling anecdote from the Freedom Riders’ appearance on the Oprah Winfrey Show in 2011 illustrates this point. Hoping to add a leaven of reconciliation, Oprah’s producers invited Elwin Wilson--a rehabilitated former Klansman who had assaulted Lewis in Rock Hill, South Carolina, during the first Freedom Ride--to share the stage with his former adversary. Understandably nervous, Wilson panicked after Oprah asked him the first question and was on the verge of bolting until Lewis reached out and grasped his right hand, calmly proclaiming “he’s my brother.” Everyone in the audience, including Ray sitting next to Lewis but off-camera, knew they had witnessed an unforgettable act of compassion and forgiveness offered by a great and good man.

Ray regards reconstructing and disseminating the life story of such a man to be a rare privilege and an opportunity to offer empowering lessons about history. “Writing for a broad audience and helping readers to distinguish between myth and reality,” he argues, “constitutes a search for a usable past. Understanding the complexity of the past--with all of its irony and nuance, its ups and downs, its moments worthy of pride and shame, its triumphs and tragedies--is essential to healthy citizenship in a democracy. Knowledge is power, and if we don’t know where we have been or where we came from, we have little chance of knowing where we are or what possibilities the future holds.”

Since retiring from teaching in December 2020, Ray has continued to write, to consult for documentary films and civil rights museum projects, and to be involved in local politics and community service, sometimes getting himself into John Lewis-style “good trouble.” He has also found more time for reading, international travel, playing tennis, going to Tropicana Field to cheer for the Tampa Bay Rays, indulging in his newfound passion for landscape painting, and most important, traveling to Washington to see his two young grandchildren, Lincoln and Poppy, and his daughters Amelia, a public diplomacy specialist with the State Department, and Anne, an attorney with the Administrative Office of the federal judiciary.

For Ray, the intense family bond that sparked his interest in history remains a source of joy and hope amidst all the turmoil of today’s perilous politics and rising threats to American democracy and freedom. Cultivating love and human connections among family and friends, he feels, is one way to bring light into the darkness. As a historian, Ray recognizes that the weight of the past can be burdensome, but at age 75 he retains a cautious optimism about life and the human condition. Quoting the irrepressible John Lewis, he reminds us that we should be thankful for each day we have on earth. “A good day is waking up!” Lewis wrote just before his death. “It’s awakening to the world and realizing the possibility that every day brings.”